At Atuka, we were very encouraged to read the topline results from the Cerevel Therapeutics Phase III TEMPO-3 trial for tavapadon, a D1/D5 dopamine receptor partial agonist.

The trial looked at tavapadon’s efficacy as an add-on to dopaminergic therapy and showed an increase in total on-time without troublesome dyskinesia of 1.1 hours a day, as measured using the Hauser diaries. (“On-time” refers to the duration of anti-parkinsonian benefit provided by a treatment.) Tavapadon also showed “a statistically significant reduction in off-time,” a secondary endpoint. While Cerevel’s results are themselves promising, their implications go beyond the possibility we might soon have a new addition to our armamentarium against Parkinson’s disease.

It’s exciting news, given how rare it is to see a new therapy for Parkinson’s progress this far—knocking on the door of the approval process. There’s now an excellent chance of tavapadon getting into the hands of patients and potentially making a difference. Tavapadon could well be providing a better quality of on-time than we’re seeing with other therapies currently on the market. While entacapone and rasagiline both extend on-time to a similar magnitude, that increase is often accompanied by dyskinesia.

What is the potential financial value here? Entacapone products—including Stalevo, Comtess, and Comtan—had annual sales of about $100 million in 2023, though that appears to be coming down a little with the new generic from Alembic now on the market. When Cerevel releases additional data from the trial in the latter half of 2024, it will be interesting to look closer at the quality of this extra on-time, to determine just how good it really is. What’s happened to on-time with troublesome dyskinesia? Based on what we have heard, it looks like off-time has been reduced alongside increasing on-time without dyskinesia.

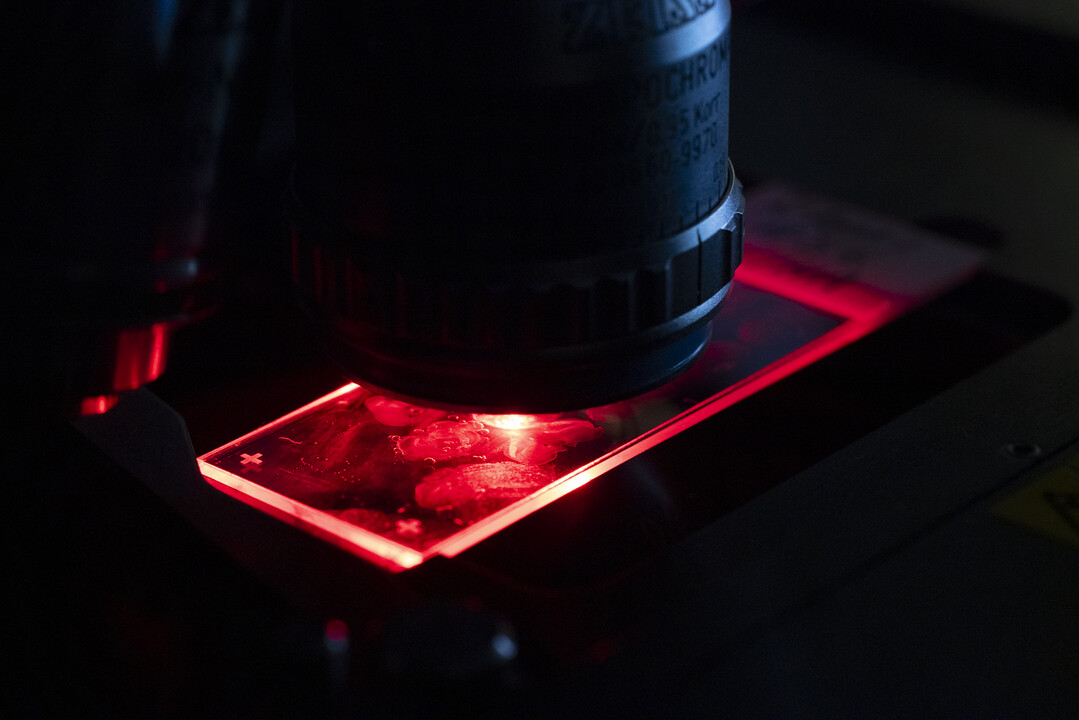

Measures of on-time in non-human primates

It’s very interesting that we’re seeing the on-time endpoint being used, again and again, positive at Phase III; on-time is one of the few endpoints we have in Parkinson’s that can be employed all the way through the development process, from non-human primates, through Phase II proof-of-concept, to Phase III demonstration of efficacy. There’s already a well-defined path for the drug’s development, one which adds significant value to the measures of on-time we’re using in our non-human primates; we like to build development paths around this type of endpoint. (For more on Atuka’s demonstration of the robust translatability of the MPTP-macaque model you can read this paper.) In Parkinson’s research we’re all too short of well validated paths for developing drugs from preclinical efficacy to the market. We’re reasonably good at developing therapies from preclinical to proof-of-concept at Phase II, but to move all the way to Phase III success is rare.

Meeting the cognitive needs of people with Parkinson’s disease

What else might tavapadon do that would be beneficial to people living with Parkinson’s? At Atuka we are intrigued by the prospect of D1/D5 partial agonists having an impact on cognition in people with Parkinson’s disease. The non-motor aspects of Parkinson’s, including cognition, are massively unmet medical needs. We have data in our non-human primate models of cognition in PD that supports the potential benefit of this class of compounds.

If tavapadon can make it to patients, there’s a very good likelihood that it won’t simply take market share from entacapone and rasagiline, but contribute to expanding the market—not only for its potential benefits from indirectly reducing the problem of dyskinesia, but by giving us a therapeutic that finally addresses cognition. Our own models of cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s tell us that that could be a game changer.

+ Follow Atuka on LinkedIn